Just Interest

Interest is a key aspect of the modern economy; its rate affects pensions, public and private investment, mortgages and savings. How could commerce and business function efficiently without being able to borrow money at interest? How could savings be directed towards their useful application without revenues from interest? Macroeconomic thinking has it that interest rates are a key lever in central regulation of an economy, dealing with ups and downs of each cycle. Although the 2008 financial crisis brought in other levers, notably QE, present efforts do appear to be towards raising interest rates and use of the lever of preference once again.

A wider perspective of the world’s cultures and history reveals that lending at interest, often termed usury, has been viewed very differently. Usury is expressly forbidden in the Islamic world, and it is only relatively recently that its many restrictions eased in traditionally Judaic and Christian cultures. It has been the subject of religious, philosophical and pragmatic debate for well over two millennia, usually resulting in prohibition. Today we may well ask ourselves if the battle of commercial pragmatism over ancient dogma has reached its final throes. Can we assume only a few skirmishes remain such as moderation of charges whilst we wait for the Islamic world to see sense? Are market-set interest rates necessary to bring prosperity to the world’s people? Have we finally dispelled any arguments of morality or justice in relation to loans at interest?

This article seeks answers to these questions by starting with a review of some past authorities; Aristotle, the Bible, Thomas Aquinas, Martin Luther, and Francis Bacon; they all addressed the subject to meet the needs of their time. This is followed by consideration of the many facets of interest in today’s world and a short excursion into the nature of money and investment. Having gathered contrasting views and ideas, sifting through them may reveal the nature of interest that makes sense for all time and all cultures, and help us distinguish what is helpful to society from anything that is not.

One of the difficulties we have to face here are words and their meanings. This will be returned to later, but for now a brief look at the words interest and usury will suffice. For much of history both were used synonymously for any charges made for money or commodity loans other than the repayment of principle. Later, their meanings diverged with usury denoting excess interest, or interest for loans for consumption rather than enterprise. The terms will be used synonymously in this article.

Aristotle

Any serious look at the subject of usury leads back to Aristotle. His surprising views on retail trade, which he categorised as commerce, usury and service, placed it at a lower level of human activity compared to household management or wealth creation.

“There are two sorts of wealth-getting, as I have said; one is a part of household management, the other is retail trade: the former necessary and honourable, while that which consists in exchange is justly censured; for it is unnatural, and a mode by which men gain from one another.

The most hated sort, and with the greatest reason, is usury, which makes a gain out of money itself, and not from the natural object of it.

For money was intended to be used in exchange, but not to increase at interest.

And this term interest, which means the birth of money from money, is applied to the breeding of money because the offspring resembles the parent.

Wherefore of all modes of getting wealth this is the most unnatural.”

Aristotle, Politics Book 1 Part X

These words have been highly influential but probably jar with today’s understanding. Rather than simply dismiss them, it may help to consider what he means. His elevated state for wealth creation can be explained as those activities that benefit society as a whole such as with food provision etc; elsewhere these are described as limited ends, simply because we can only eat so much, there being a natural measure. His dim view of retail trade can be seen through relationships between people where one gains at the expense of others, “zero-sum-games”. This may reflect the practices prevalent at the time. As one example of later thinking, Henry George went to great effort to distinguish created from acquired wealth; his analysis showed aspects of retail trade to be very much part of wealth creation.

Aristotle emphasizes the most important aspect of money is as a medium of exchange. No amount of money has the power to grow despite frequent financial advice to the contrary. Hence Aristotle sees money as sterile, unlike cattle or crops which have nature’s power to reproduce. Hence interest is not in the nature of money itself.

Deuteronomy

For Europe and indeed much of the world, another great influence has been Judaism and Christianity. One of the most frequently quoted references is Deuteronomy 23: 19-20.

“Thou shalt not lend upon usury to thy brother; usury of money, usury of victuals, usury of any thing that is lent upon usury:

Unto a stranger thou mayest lend upon usury; but unto thy brother thou shalt not lend upon usury: that the LORD thy God may bless thee in all that thou settest thine hand to in the land whither thou goest to possess it.”

Deuteronomy 23:19-20

Usury is usually associated with money loans, but traditionally has also applied to commodities such as wheat; any transaction where one gained at the expense of another could be included. Perhaps surprisingly, usury is OK with strangers but not to ones brother. In practice this was taken as a brotherhood of all Jews who could without sin lend at usury to Christians. But how can usury itself sometimes be sinful and at others not? One possible interpretation is that brother refers to family which can healthily be considered as the smallest economic unit; relationships between family members are closer to unconditioned love than a negotiated trade.

Commercial Pressure

Christianity and Aristotle remained highly influential for many centuries, perhaps something that is difficult for us to appreciate today. Usury was a sin and you really did not want to get caught, even if you found it necessary or desirable to practice it. This presented difficulties in a post-Roman world where trade and commerce was flourishing again. Each ship’s voyage needed financing and all enterprise involves risk; Popes and the more temporal rulers were often short of money; so where was the money going to come from? Luckily Deuteronomy allowed the Jews to step in; others had to help during the various periods of Jews’ banishment.

Then as now, financial innovation could be counted on to come up with solutions that ensured that the authorities could not mistake money transactions for usury. One such scheme featured pairs of complementary foreign-currency-exchanges with different rates that yielded suitable profit for the lender; these were sometimes called “dry exchanges”, especially where the currency exchanges were on paper only.

An ingenious arrangement showed itself as a written interest-free loan contract with defined penalties on default; for example, a principle of £100 is to be repaid ten months from now, but any default will mean that £130 has to be paid 12 months from now. The unwritten agreement was to always default, yielding 30% “non-usurious” return for the year’s loan.

Annuities were another technique for financing public or private projects for profit without usury. The advances were made in exchange for future income in the form of rents, generally not related to the investment.

Bills of exchange also helped obscure any sense of interest payments in transactions involving a merchant bank; they use the concept of discount rather than any additional charges for interest. Effectively, the money borrowed is returned without interest; however, what is received at the point of borrowing includes a discount.

Aquinas

Another significant influence was St Thomas Aquinas. Many arguments in favour of usury had been voiced over the centuries since Aristotle. Aquinas collected these into four general areas: charging money interest; non-money charges for loans; repaying usurious gains; and borrowing under usury. For each, he carefully formulated counterarguments often with reference to Aristotle. He maintained that usury was a sin against justice itself, as it was charging for something that did not exist (echoing Aristotle’s money having no ability to grow). He argued that additional payments made in anything that money could be exchanged for was much the same. However where a lender incurred real costs or losses through making the loan, this could be charged for. Interestingly it was ok to borrow at usury if used for a good purpose.

“To take usury for money lent is unjust in itself, because this is to sell what does not exist, and this evidently leads to inequality which is contrary to justice.”

“… just as it is a sin against justice, to take money, by tacit or express agreement, in return for lending money or anything else that is consumed by being used, so also is it a like sin, by tacit or express agreement to receive anything whose price can be measured by money. ”

“A lender may without sin enter an agreement with the borrower for compensation for the loss he incurs of something he ought to have, for this is not to sell the use of money but to avoid a loss.”

“It is by no means lawful to induce a man to sin, yet it is lawful to make use of another’s sin for a good end, since even God uses all sin for some good…”

Thomas Aquinas – Summa Theologica part 2 Q78

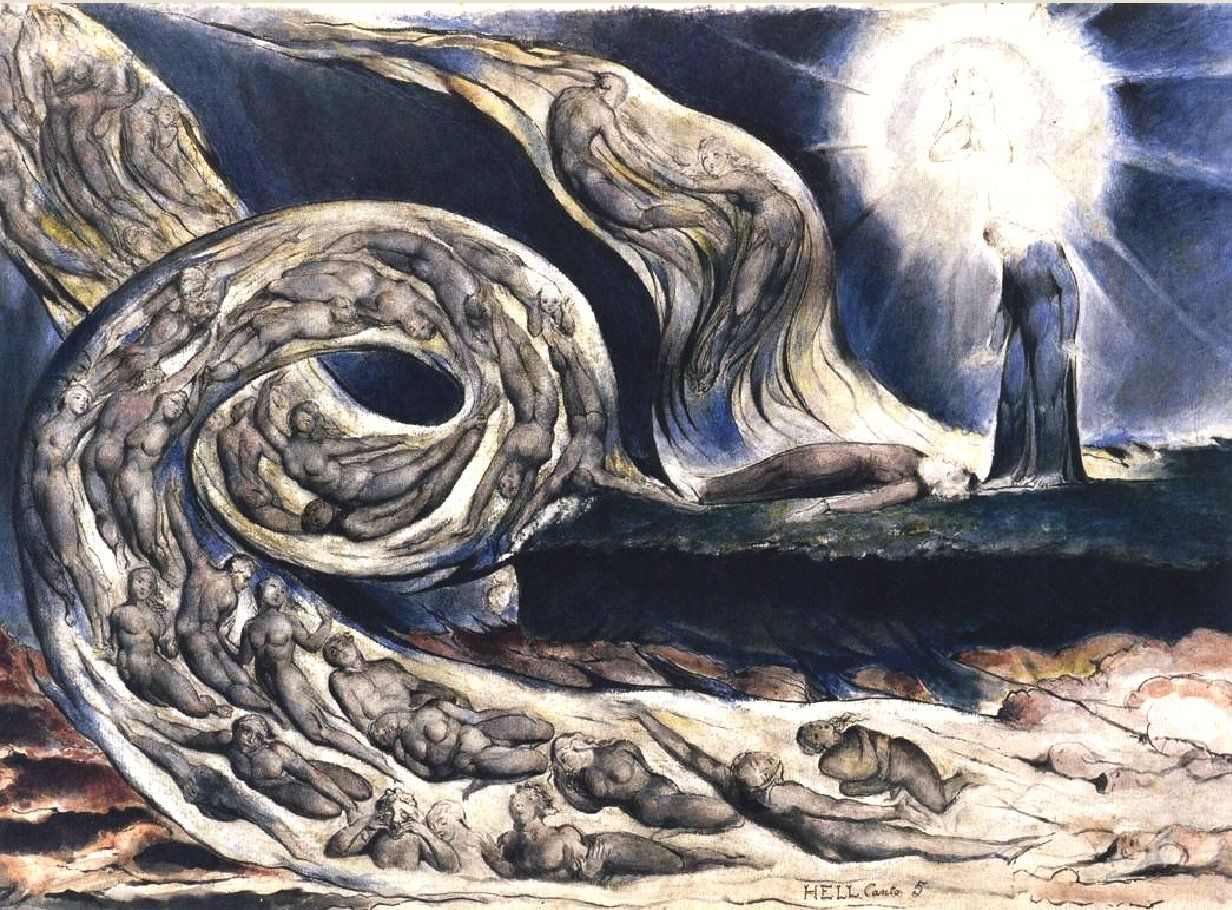

Dante

Aquinas’s influence ensured the general ban on usury was maintained for a several more centuries. But how sinful is usury? To get a sense of its reputation in these times we can see where Dante positioned its practitioners in his inferno, depicted here by Bartolomeo Di Fruosino c 1435. The main gates descending into hell are in order Limbo – Lust – Greed – Heresy – Violence – Fraud – Treachery. Usury in behind the gate of violence which distinguishes three areas that violence targets: people and property; life (suicides and profligates); God and nature. Usury is an aspect of violence against God and nature and is the most sinful of the three examples: Blasphemers – Sodomites – Usurers. Usury was believed to be the very worst form of violence, worse than heresy. Aristotle’s point of money being sterile by nature may help explain this; if an increase (usury) was superimposed on its nature, or a charge made for God’s gift of time, this would be a sin against God and nature.

Martin Luther

Martin Luther re-enforced the general ban on usury. A sense of where he was coming from can be gleaned from how he described trading relations between persons; following a surprising statement on honesty, he defines the four legitimate forms of Christian trade.

Luther takes honesty much further than any feelings we may have of honesty being a vital aspect of good trading practice. Trust God before men; men sometimes err from being honest and hence it is better to trust “that which never errs”. We may wonder what he means, but could get a clue from a little reflection on our dealings with other people. Perhaps we are able to literally keep complete faith in God; perhaps we can trust their more godly aspect such as their humanity; perhaps we can connect with a sense of unity embracing both. These may hint at what he means in trusting in that which does not err rather than an occasionally erring character.

Luther’s four Christian forms of trade also challenges our modern understanding of trade:

- If someone takes your cloak, give them your tunic as well.

- Give without charge to whoever is in need.

- Lending is ok where there is absolutely no expectation of return (pay-it-forward?).

- Then thankfully there is a form of trade we can recognise, cash buying and selling. However, these are spot-cash transactions; no credit terms and corresponding debts to pay.

Bacon’s Pragmatism

Francis Bacon gave us the scientific method, and lent his practical mentality to the very real problems of usury of his day by assessing its relative problems (discommodities) and benefits (commodities). Discommodities included an increase in both inequity and poverty; commodities included encouragement of commerce through finance and easing life’s ups and downs through the occasional loan. His judgement came down in favour of usury; however this was based on constraining interest rates to households at 5% and facilitating the greater needs of merchants and their riskier investments through licensed lenders. He wanted to “grind the teeth of usury” but use its benefits. Although regulation and practice did not quite settle in this way, it does represent the general direction for the future, as does the lack of reference to scripture or moral in the argument.

Life Continues Today

Life continues and its costs were supported through loans, despite the general prohibitions. Jews were able to lend, and Christians were able to borrow. Lenders always run the risk of becoming unpopular and were only sometimes protected by law, Jews were outlawed much of the time. Whilst accepted, their trades were often restricted to moneylending and doctors. The possibility of avoiding loan repayments probably encouraged their expulsion. In England, Jews were expelled in 1290 and were not allowed to freely return until 1829.

Italian merchant families and banks were able to provide finance for a time. A few English kings defaulted here as well, taking down some of the banks. Wealthy merchant families were able to facilitate financial transactions across Europe and beyond with bills of exchange being a key financial instrument. Trust within an extended and well-placed family was an important factor, and such merchants could become much wealthier.

Gradually usury laws made lending at interest easier. Netherlands 1540 permitted 12% on commercial loans; Henry VIII 1545 permitted 10% on all loans, later modified several times until restrictions were removed in 1854. US lagged Great Britain in removing usury restrictions; this was especially for its national banks which helped London take the lead in the Eurodollar trade and become the leading currency market today. In the period where some US states had less restriction on others, it helped determine where financial organisations were located. Of course modern banking has no hesitation in charging the highest possible rates, it being merely the operation of supply and demand.

Islam continues to forbid usury, and there is something to learn here from this. The general word for interest is Riba, meaning increase; riba is forbidden, and manifests in two ways. Riba-al-fadl is where one party gains at the expense of the other in like-for-like transactions.

“Gold for gold, silver for silver, wheat for wheat, barley for barley, date for date, salt for salt, must be equal on both sides and hand to hand. Whoever pays more or demands more (on either side) indulges in Riba.”

Riba-al-nasiah covers transactions involving time; the four characteristics of time-separated trades are significant:

- fixed and guaranteed

- increases with time

- secures lender; exposes borrower

- does not increase with Allah; invites his anger and wrath

We can see that where the deal is fixed in advance, especially under pressured circumstances, life’s inevitable uncertainty will tend to expose the borrower to risk and keep the lender secured. If the charge is greater for longer periods of time, this is a charge on time which is not man-made. To understand what is meant by the “charge not increasing with Allah”, it is helpful to consider that the more pure-hearted transactions are less likely to involve higher charges; higher charges are most likely associated with less pure hearted motives which are to an extent sinful; hence only no charge for money loans can be sinless.

Compound Interest

Compound interest is now so much the norm that we may overlook that it has not always been so. There does seem to be some confusion surrounding compound interest. This has in fact been the case for many centuries, and only become clearer with the publishing of calculation tables in the 16th century. For example, one myth propagated today is that compound interest necessarily leads to an ever greater money supply. To help demystify compound interest we can return to Aristotle and imagine that shortly after writing Politics he invested 1p at 1% interest under 3 different regimes of interest as represented in the table.

The first is simple interest which would accumulate to a debt of 25p today. The second is compound interest which accelerates to astronomical debt today, increasing by more than £1million each year; this is obviously extortionate and fuels spectacular claims and myths. The third example is still compound interest, but where a modest payment of 1% is made; this exactly matches the case of simple interest in terms of overall outlay. Most fantastic claims regarding compound interest assume no repayment; the small print is always important. Perhaps the main problems of compound interest are the almost universal belief in its being a natural part of lending money and its abuse.

| Years | Simple | Compound | Compound + repay |

| 1 | 1p | 1p + 0.01p | 1p |

| 10 | 1p + 0.1p | 1p + 0.105p | 1p (+ 0.1p) |

| 100 | 1p + 1p | 1p + 26p | 1p (+ 1p) |

| 1000 | 1p + 10p | 1p + £209.58 | 1p (+ 10p) |

| 2337 (today) | 1p + 23.37p | 1p + £125,617,611.08 | 1p (+ 23.37p) |

Comparison of Interest Regimes

Nature of Money

Money is very much the medium of interest and warrants some consideration. The healthiest way to view money is as a readily accepted medium of exchange. We accept it in exchange only through knowing someone else will accept it in exchange for what we really want. It is a token of trust, and this trust is of the whole nation. We would be much the poorer without the facility of money.

Money’s pre-eminence in exchanges makes it a useful measure of value of tradable things, making it a unit of account. Pricing does not need access to money, but buying them certainly does.

Money is often seen as a store of wealth, and this notion greatly confuses economic analysis. It also underpins any notions of its being lent rather than kept held in the hand warrants compensation as interest.

Creating Money

One aspect of money that stirs emotions over interest today is of its creation. Perhaps rather surprising to many, most money is created by our high street banks when we want mortgages or other loans. Our agreement to repay underwrites the banks ability to create new money and lend it to us. This accounts for some 90% of UK money, which is the sum of all loans less sum of all repayments, about £1.7 trillion. The nation effectively pays the commercial banks interest on the nation’s money supply. In practice banks get the net interest, which is interest paid on loans less what the banks pay out on deposits. As money creators, they have to attract sufficient deposits to balance the books, and this may involve interest payments.

One concern is that this money supply is invaluable to the nation, and the profit-orientated money-creating banks could be charging more than the cost of service provided, owing to their somewhat privileged position. Market players with any significant monopoly power are able to raise prices significantly above costs, one of today’s challenges in many areas. This has led to calls for money creation to be effectively nationalised to avoid conflict between profit and public benefit. History can remind us of the long-term periods of rulers abusing their control of the currency through debasement or inflation. Great care is needed to avoid either private or public abuse of the nation’s money supply.

Inflation

We fear inflation, but fear deflation even more. Inflation is a measure of changing relation between nominal money, say £1000, and the goods, services and other entities it can buy. Expressing inflation as a single figure is extremely challenging and relying on such figures can be misleading. For example, do the rising rents paid by part of the nation to the rest get captured?

Interest rates are highly sensitive to inflation; loaning £1000 for a year in 10% inflation will only return to lender without loss of purchasing power if interest was set at 10%. Interest rates are described as “nominal” when inflation is included and “net” when the element related to inflation is removed.

Purpose of Loans

It has long been recognised that loans for consumption are less wise than loans for business. Loans to households to make ends meet till payday often make things worse; in desperation, onerous terms can be agreed to which result in their supporting the rich with no hope of escape. The relatively modern phenomenon of a consumer boom has been fuelled by innovative ways of presenting debt; store-based credit terms, hire-purchase and now credit cards, all being supported by vast advertising campaigns for consumption. Getting into debt now seems to be an attractive proposition rather than a necessary evil; nevertheless, paying back loans will always involve forgoing future consumption, the iron rule of borrowing.

In contrast to consumptive loans, loans for enterprise are instrumental in establishing new business and hence new means to repay them. This is the healthiest form of investment. Where new enterprise increases the national level of economic activity, creating new money is wise as it supports the additional goods and services being exchanged. However, where no net increase in economic activity is likely, an increase in the money supply is generally unwise.

The third general purpose of loans is less healthy but unfortunately the most widespread, loans for assets and in particular land as property. Rather than create new wealth or sources of repayment, it affects who gets the benefit of pre-existing wealth by redirecting economic rent flows, and tends to drive up asset prices.

The money supply for a nation needs to grow or shrink as the level of economic activity grows or shrinks. Recent decades have seen a money supply increase easily outstripping the rise in goods and services; thankfully this has to date supported asset inflation such as for land prices rather than high inflation of goods and services. Banks in this way have managed to gain a share in the economic rent of the nation’s land.

Microcredit

It may be helpful to consider where a relatively high rate of interest does not seem to be unjust. For this we can look to the excellent example of escaping the grips of moneylenders through the agency of the Grameen bank, the first microcredit institution. During a famine Mohamed Yunis as economics professor spent time investigating the plight of the poor. He met a mother virtually slave-bound to a moneylender that was the only source of funds to buy materials, but the loan condition meant that the stools she made could only be sold to him. She earned US$0.02 per day, and was thereby kept at subsistence level! From this observation evolved the Grameen Bank and microcredit. Without written contracts or collateral, trusting only in the integrity of the poor, using the strength of village community, notably of women, a system of small loans to be paid in weekly instalments for a year began. It mushroomed and lifted many out of abject poverty. Their savings are typically banked with Grameen and earn interest. Savers own Grameen as it is a not-for-profit bank. Now interestingly, especially given it is a Muslim nation, they charge 20% interest; and yet the borrowers thrive. This rate pays for the costs of the bank’s intensive support for the various communities managing their enterprises. Both the moneylender and Grameen can be seen to charge interest; are both sinful, or is there a sin-free aspect of interest that needs to be discovered?

What do we mean by Interest?

It is now the moment to consider more carefully what we mean when using the word “interest” and for here synonym “usury”. Deuteronomy seems to imply usury is sometimes a sin but perhaps not sinful at others. Aristotle is adamant but commerce benefitting the community appears to prosper where interest is permitted. The moneylenders were displaced by Grameen but interest was transformed rather than removed.

It is as though the words “interest” and “usury” have very different meanings when they applied to Grameen and the moneylender, or to the two verses of Deuteronomy, or for Aristotle and the purveyors of commercial prosperity. Economists have searched for a cause or natural origin for interest; if a natural cause or law of interest exists, how can it be sinful?

One note of caution is that the term “interest” has been used as either the profit associated with lending money as assumed for this article so far, but it has also been regarded as the profit or return on capital. A second note of caution is on the word “capital”; economic capital is tangible wealth such as machines, buildings and roads; financial capital is any form of financial asset which includes and is assumed to be commutable with money. By failing to keep these meanings separate, the significance of economic capital is lost. However, here we have to embrace both senses of capital, not only as they are often believed to be interchangeable, but also to understand what these economists were seeing as interest.

Bastiat suggested interest is due to the power in physical capital or tools to increase the productivity of labour. This can be challenged by pointing out that free market competition would naturally disperse any concentration of such power in tools as they would become commonplace; any ability to charge a premium imply the presence of market restrictions or property-right claims.

Bohm-Bawerk suggested interest was due to a natural time preference for using the good today rather than next year. Whilst the potential borrower’s preference is clearly to spend today rather than next year, this commonly held belief also implies the potential lender’s preference to spend the money next year rather than today. If so, the potential lender could gain by actually paying for the money’s safekeeping for a year! Hence, risks aside, a loan at zero interest would still be of mutual benefit. Thus any charges over coverage of risk must be due to the relative negotiating positions of the parties involved and not to any natural time-preference.

Marshall suggests interest is a reward for frugality in deferring consumption till a later time. Although this may seem to make sense, let’s dig deeper. Does it make sense that a potential lender is rewarded for frugality whilst the potential borrower is to be penalised for investment risk? Society at large would be immeasurably poorer without innovation and development, and also the poorer where some have too much and others not enough. Hence it may be argued that sitting on spare cash should be penalised rather than making good use of it? Some forms of money used to attract stamp duty to encourage money circulation; this was as though all money were borrowed at interest from the government.

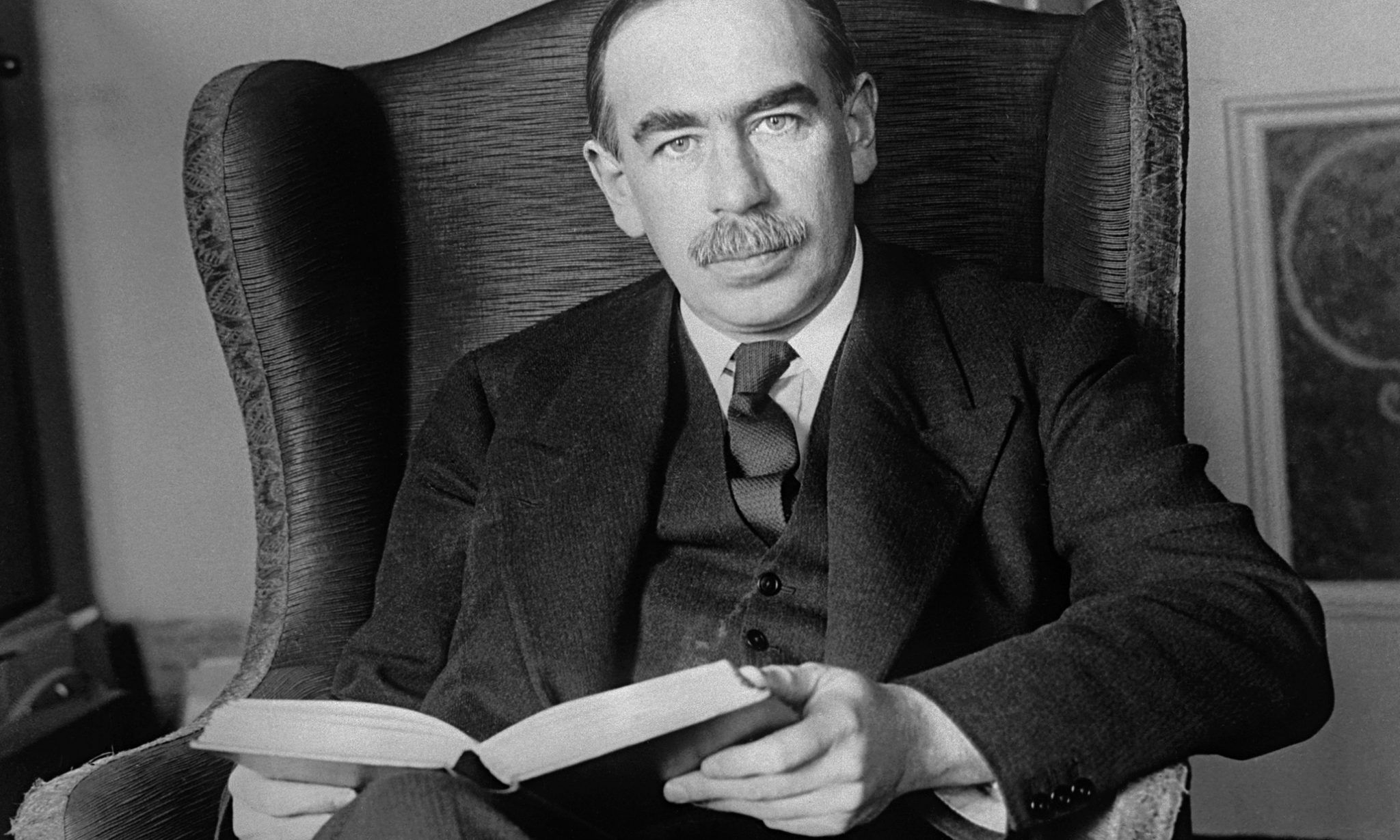

Keynes saw interest as an indication of the future’s uncertainty and illustrated this as a seesaw between bonds and money. Speculators buy bonds on the expectation of falling interest rates and sell them if rates are expected to rise. This is due to a market-led alignment between the rate of interest and the return on holding bonds being the coupon based on nominal bond value rather than its market price. Low interest rates give similar returns to coupons when bond prices are high and vice versa. Hence expected falls and rises in interest rates correspond to expectations of rising or falling bond prices, and hence the speculation.

Good guessers win over those lesser able, but no one knows for certain, especially over the medium to long-term; hence some money is always held both as a precaution against unexpected asset failure and for unexpected speculative opportunities. Hence bonds have to offer sufficient returns to attract money and this effectively sets a general rate of interest. However, this relates to the speculation with money well in excess of that needed for the nation’s exchange of goods and services. Although important, is is not possible to do justice to this aspect of interest here.

Henry George wrote on interest in the sense of a return on capital. Nevertheless his great guidance to us is his insistence that what we called an interest charge was examined carefully. If we accept legitimacy of a money-lending business that serves the community, what should it charge and be paid for? Those managing the business need wages; the business has service and building costs, and its landlord will need rent. All of this will have to be paid for by the lenders, and it may be seen as equitable if the charge was proportional to the amount borrowed and the period of loan. It could be called interest or service charge. On top of this is the question of risk; somehow the business has to charge a premium to make up for defaulting losses. Again, the more risk the more premium.

It is worth remembering that fees are often paid as well as interest, and the total charge does include both. However, if this charge was in excess of costs, or the penalties of default were in addition to any premium already charged for risk, then the negotiations over the loan may not have been free; some form of privileged position is likely to be meeting a deprived one and the terms of agreement settled accordingly. Traditionally debtors are rarely forgiven, with the force of law even depriving them of any livelihood through imprisonment. Really free negotiating positions are where borrowers and lenders are both able to say yes or no.

Conclusions on Interest

To reach a conclusion we have to return to the starting point where interest is the charge for borrowing money. To really make sense of this, arrangement fees need to be included as part of the charge.

Injustice prevails where the charges exceed the costs of providing loan service, including allowance for risk; it is also present when conditions are such that people are forced to borrow money. Aquinas allowed legitimate costs to be charged, but prohibited conceptual costs such as opportunity cost, a subject that warrants further consideration.

We live on one planet earth as have our ancestors and will our descendents. Our acquisitive aspirations often exceed natural measures and hence scarcity. Economics becomes necessary to allocate these scarce resources amongst competing aspirations. Without wise application of just economics, we are left with might is right. This becomes a property frenzy separating haves from have-nots. What can be common interest becomes a series of divergent interests as inequality develops.

Governments have the power but not the inclination to move taxation towards privilege rather than enterprise. In the more democratic societies, education could but does not explain the effect of privilege without responsibility; this affects government policy.

In the meantime privilege manifests as being in command of considerable debts, pools of money, acres of real estate and the means of tax avoidance. Injustice in charging for loans is really as aspect of a much wider issue that needs to be faced.

Do we have any option to make interest and our other economic relationships more just?

Rather than simply point a finger at government, bankers and the like, perhaps we should start at home. Then we can see more clearly the issues involved and support societal movements for change. And so here is the 3 point plan to bring justice to interest:

- Cultivate a fresh lifestyle, moving towards living within ones means and moderation of some of our desires. Happiness being based more in self-contentment and less in consumption and gadgets could reduce the tendency towards debt and resulting interest.

- Collectively begin to see privilege and ownership as necessarily being balanced through obligations. Discourage all aspects of exploitation at the expense of others such as through onerous property rights in their various forms.

- At the national level of government move taxation away from enterprise and towards privilege where this is not balanced by obligation. The dominant need is to implement some form of taxation of location value as with LVT which is the dominant driver of inequality. This can be usefully supported through improved means of charging banks for their particular privileged position.

It may seem rather of a tangent to advocate LVT or similar as a means to tackle excessive interest charges, but, it is a fundamental point. Economic rents flowing through society from those without to those with, and land-economic-rent being the dominant but not only form, create pools and dearths of money and encourage the need for money loans.

The move towards property-based taxation has recently been advocated by the IMF and the Nobel Prize winning economists Joseph Stiglitz. It would tend to increase household prosperity reduce government deficit, and reduce the need demands for loans.

As a final conclusion, it would seem that the sin associated for so long with interest is more to do with the exploitation of the weaker by the strong. If it were simply man’s nature to exploit the weak, this could not be a sin. However the human being is capable of working in such a way that benefits the whole of society rather than some at the expense of others; it is choosing to not work in this way that makes it a sin. Let us be encouraged.